Cairo 360

The term refugee is often associated with loss, tragedy, and diaspora. Adding the term ‘female’ in front of the word ‘refugee’, only worsens the aforementioned association: concepts like rape, and an increased likelihood of living in poverty, are realities that effect female refugees more so than they do their male counterparts. Our favorite thing, however, about the album entitled Shagara (Tree in English), is the fact that it draws us away from mere victimization, and pulls us towards a more realistic and complex understanding of female refugees. Indeed, the album has given a group of female refugees an opportunity to become active writers of the stories they tell (via the songs they wrote/sang) within this album.

The beauty of this album lies specifically in its capacity to highlight the fact that narratives are rarely – if ever – entirely tragic, and/or victimizing; the female refugees behind this album are more than just singers/songwriters, they are genuine auteurs. As such, The Hello World Choir was able to produce music that in a way resembles life itself, with all its astoundingly complex elements.

Here is what Maria Sideri, the artist who initiated the project, had to say about the it.

Q: The female body – especially the foreign one – is an element that seems to be central to your work? Why is that? Can you elaborate more on how this element has inspired the work in this album?

A few years ago, I discovered a book by anthropologist and artist David Napier titled Foreign Bodies, Performance, Art and Symbolic Anthropology. Napier demonstrates through various examples from art to biomedicine, how the concept of the foreign body plays an important role in shaping cultural identity. Working between performance and choreography, with a background in anthropology, the theme of the foreign is recurrent in my practice. When we accept and respect that the foreign is embodied in a culture and that it is functioning inside and not outside of it, we also accept the way it informs and changes the understanding of our own body in relation to others.

I arrived in Egypt to explore the life and times of a 1930’s avant-garde artist, journalist and feminist thinker Valentine de Saint Point. Saint Point also worked alongside renowned Egyptian feminist Doriya Shaafik whom I discovered in Egypt, and who has worked on issues of woman’s rights and founded the feminist organization Bint Al Nil. During my stay in Cairo, I was so inspired by these women I wanted to collaborate with a local female community and explore notions of ‘the foreign’ or ‘the outsider’.

The Hello World Choir was originally initiated through a residency with the Townhouse Gallery between October and December in 2015. During my residency I met the visual artist Amado Alfadni who put me in contact with Tadamon (Egyptian Refugee Multicultural Council) in Maadi. I visited the center, met the girls & the young women, and we formed the choir. Through a continuous body of artistic work that encompasses music, performance and writing, my investigative dialogues with this small part of the Sudanese community of Cairo, brought me towards re-thinking notions of the female foreign body and how it manifests itself in the rich and complex diversity of today’s immense cityscape. Through composing this music and the texts with the choir, an empowering space for young women’s collective, and for myself, emerged. By sharing our personal experience and creating this work, we made and marked ourselves visible from the hidden neighbourhoods of Hadayek in Maadi.

Q: In what ways does the name “Shagara” relate to this album?

Having done some research before I propose to the group to write some lyrics about a tree that they love, I discovered that trees for Sudanese people play an important role in history. In their mythologies, trees are considered to give birth to people, like the sacred tree Rual that possesses a spirit that gave birth to humanity from an insect. I have also discovered the significance of the Akoc trees that functions as a space for remembering important historical events.

When we wrote the lyrics to this song, everyone contributed a line and the introduction was made later. The first part of the song Shagara is a traditional Sudanese song

( لو اعيش زول ليهو قيمة ) that speaks, among other things, about the freshness of a tree branch everyday day getting greener, and that offers its shade for people to rest.

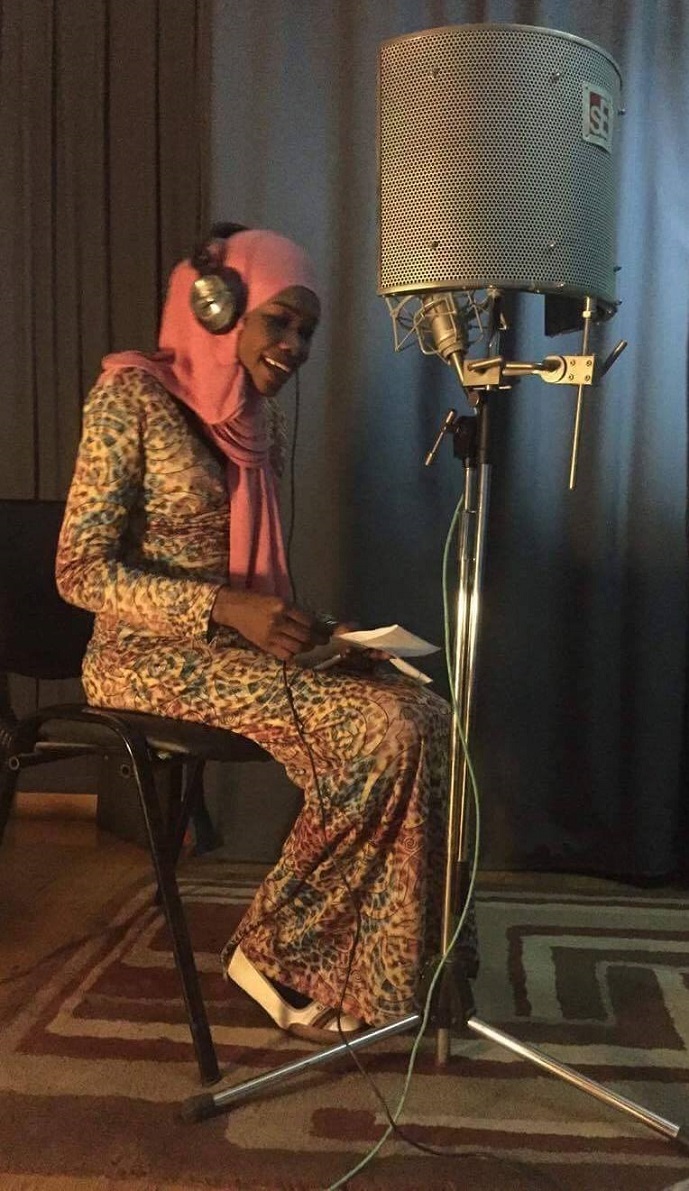

When we first recorded Shagara, we had an appointment to go to the recording studio. Everyone was very late and I was waiting anxiously for over an hour to take them to a studio in Haram. At this moment, when I was almost ready to leave, Abeer showed up and sang this song to me. I didn’t know her at that time, but I was amazed by her voice. Abeer is an incredible singer, who used to sing in a choir in Khartoum. I asked her to join our choir, and we recorded her voice singing the intro to Shagara. I am so grateful for this! Our tree is our album Shagara, it gave us a space to gather, and make this music.

Q: Why the mixture between English & Arabic?

The girls and young women in the group were from Yemen, Ethiopia, and Sudan. Some of them didn’t speak Arabic, some of them did speak but did not write, and some didn’t speak any English. To truly collaborate, we collectively had to learn the words of the songs by means of expressing the lyrics in both languages. That way we could all learn the same lyrics and understand each other.

I wrote the lyrics to Hello World, Eman Abed El Waged penned Wake Up, and Nour Mustafa Mussa, a Syrian refugee that was engaging with Tadamon, wrote Little Dream. Shagara was a full collaborative effort. When we translated the songs into English, and into Arabic, it worked for everyone: everyone understood and participated in the learning. We worked in groups so that everyone could teach others and learn at the same time. The group also taught me a lot of Arabic words, and we had a lot of fun and laughs with me trying to speak it in the beginning. They definitely helped me get better though!

Q: What do you think is the element that ties the narratives of all these women together, besides their status as refugees?

Of course as young women that moved between and across borders, they have shared a similar experience. All of them have a story to tell, often attached to traumas that I chose not to emphasize or explore further in our work together. I wanted to generate a different kind of space away from all of that. I never asked them about their personal experiences of how they got to Cairo, and what they might have left behind. It’s shocking that 60% of the population fleeing war in Sudan are children – and mostly girls and young women.

As far as their refugee status is concerned, this is temporary, but something that society generally uses to describe them. This is often unhelpful and too simplistic, especially when I think about how rich their lives have been in other ways. Most of the women and children are integrating slowly into their new society, yet Egyptian society still remains discriminatory, and the women face many difficult problems. I was keen on supporting and empowering them, to help them overcome this temporary status, and focus instead on what inspires them.

Within a short amount of time we wanted to create, own, and share other narratives. Ones that speaks about dreams, strength and hope, not based upon narrower definitions of trauma and victimization. Instead, we wanted to build narratives that were dynamic and delivered a message to the world that said/says “whatever will come for me, will come for you all”. This work gave me a lot of hope and courage; despite the difficulties these young women and children have encountered, with motivation and hard work they can still achieve great things and fight for their dreams. This album is a great thing.

Q: When you work outside the mainstream music industry there are benefits and there are obstacles, so why choose to work outside the mainstream? What are the benefits that you reaped from, and what are the disadvantages?

Music has this great capacity to speak universally. Making these voices present and audible, was the most important thing for me throughout this entire process. I wanted for us to demonstrate and share our collective skills, despite our relative invisibility in the city. Music created a space for contesting discrimination, and celebrating our protected characteristics. It is this that I focused upon, and less so on choosing which industry, or even art form genre.

Of course, we have to play along with what is offered today in some way, and Shagara has been released and distributed on Spotify, Itunes, Amazon and other platforms. However, there are a multitude of benefits to working within a grass roots community movement like the Hello World Choir; a movement that creates its own contexts and does not necessarily serve what is needed/demanded in order to sell records. Working independently and outside the norms might be a lonely process sometimes, but there is greater freedom in making your own choices. And so the outcome is the product of the circumstances, and working with amazing sound engineers, producers and musicians in Cairo has been extremely rewarding for me personally, and gave the album a very fresh and distinct sound. The result is definitely the outcome of a broad collaboration with everyone that has been part of this album and its journey.

In terms of disadvantages, I should be clear here that from its inception, through creation, mastering, and release, Shagara and the choir has received no financial support. This is why it’s crucially important that people contribute and purchase the album, so that we can continue to work with this choir as an ongoing collaborative project. I am planning to return to Cairo soon to make a video-clip with the group, create new songs and, hopefully, a performance.

Q: Female stories often get dismissed as too emotional or too irrelevant, despite of this the entire work centers on female names and narratives, between the former and latter, what is the message that this work seeks to send regarding female narratives?

I chose to work with a group of girls and young women to address the difficulties encountered by this particular group within society. Doing this, doesn’t mean that I neglect or dismiss the importance of working equally with the male community. Often this separation creates problems of discrimination. Specifically, for this group though, most of the girls live with their mothers and sisters that fled the war, and so they are used to living in purely female environments.

This collaboration wants to harness and use the power found within such a unique group of women, especially as they encounter issues related to their professional path, their integration into a new society, and the ways in which they are seen from and by others, specifically in a country that is extremely patriarchal. Their narratives are important, because they bring suppleness along with power. It has to do with their upbringing, the obstacles they encounter as women and how they overcome them.

Q: Do you think females have experiences unique to men when it comes to diaspora and/or migration? If yes, how so? If no, why not?

Women that move between and across countries encounter different challenges, related to rape and sexual abuse, trafficking and violence. This is something that is not being said and discussed enough, given how widespread the problem is. Most of these problems continue for the young women and girls, even when they arrive to a safe haven. Indeed, adult refugees in Egypt, even those that have received higher degrees in their home countries, only have access to employment opportunities in the informal economy.

For women this is very difficult, especially for single mothers, who tend to receive less payment for their work than men, and are forced to work in roles where they may be particularly subject to abuse. In many cases women, unable to sustain their families, find themselves tempted to return to their home countries, despite the enormous risks of doing so.

The lack of access to public education prevents young immigrants from completing their education, and threatens their ability to participate in the formal economy. All these issues create tensions between this community, and Egyptian citizens, who often look at refugees with mistrust.

Q: What have you learned the most from working on this project?

Primarily I have learnt, or rather just started to learn, how to collaborate with teenagers. This has been a very important part of the process for me. Learning how to keep the young women interested and engaged, and how to deal with the obstacles of language by trusting non-verbal communication, are all things that I have learnt. I also learned how to drop my personal expectations, and respect the challenges that this community faces.

I inevitably learned a lot about making an album through working with amazing musicians. From sound engineers Mazin Helal, Kareem Captan, Peter Ayman in Cairo, to Tasos Korkovelos and Anastatios Kokkinindis in Greece, to Ibrahim Ezz El Din (who has been a pioneer in this project and added to our music amazing guitar lines), to Ahmed Omran and his gambri, flutes and aoud, to Mazin Helal who did much more than just recording, and finally to Ahmed Darwish and Faddy Yanny who contributed so generously to the project with percussion; I was surrounded by inspiring artists.

I mostly learned that when people converge with meaning, a lot can happen!

You can support this project, by buying the album.

recommended

Cafés

Cafés

Bite Into the Croffle Craze: The Best 5 Spots to Try Croffles in Cairo

cafes cairo +2 City Life

City Life