-

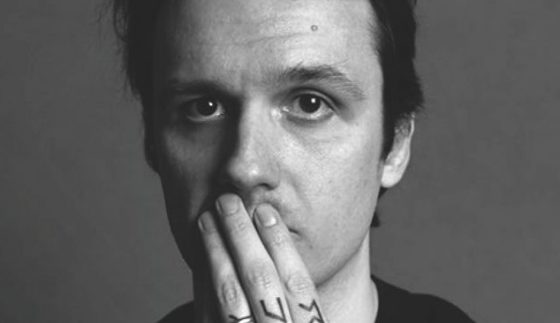

Damien Echols

-

Biographies

-

Out now

-

English English

-

140 EGP

-

Everywhere

Ester Meerman

Echols grew up as typical ‘white trash’ – a term he uses to describe himself throughout the book – in a trailer park in a small town in Arkansas. Poor as a church mouse and with a minor criminal record for vandalism and shoplifting, he always wore a black trench coat and sported an alternative hairdo. There were rumours going around town he was into satanic rituals. When three boys were found dead in the woods, he was an easy scapegoat for the Arkansas police force.

His friend Jason Baldwin and another kid who lived in their neighbourhood, Jessie Miskelley, ended up as collateral damage for hanging out with Echols at the wrong place and time and were sent to prison for life.

After a prizewinning documentary about the boys’ case – now dubbed as the West Memphis Three, or WM3 – attracted a lot of attention. An alternative defence team was put together that would eventually free the three men, but only after having spent over half of their lives in prison.

“I will not give in to anger”, he writes. “If I do, then they have won.”

Raised a Christian, Echols goes on a spiritual quest to give meaning and structure to his life behind bars. He describes his days as “a dark and distorted version of monastic life”, spending hours meditating and reciting bible verses.

Having experienced it from the inside, Echols is very critical of both the American judiciary and its prison system. He describes the conditions in US prisons as a mix of “sadness, horror and sheer absurdity.” Echols concluded that “jail is preschool” and that “prison is for those earning a Ph.D. in brutality”.

Many of his fellow inmates go mad. He remembers a fellow prisoner that Scotch taped crickets to his body, calling them his ‘babies’. Another death row convict was so far beyond sanity that he couldn’t be made to understand that finishing his dessert after his execution was not an option.

The West Memphis Three were eventually acquitted on Alford pleas, which allow them to assert their innocence while acknowledging that prosecutors have enough evidence to convict them. In his book, Echols understandably seizes every opportunity to proclaim his innocence. Every time this prison sentence comes up it is followed by his assertion: “For a crime I did not commit,” as if to nullify the court decision. Now, as true as that might be, it does get tiring to read.

One good thing to come out of this whole experience, Echols recognises, is that he became an autodidact in jail. He was a high school drop-out when he came to prison, but managed to cultivate his intelligence and vastly expand his knowledge by reading thousands of books on a wide variety of subjects during his time there.

This certainly shows in this book; fluently written, it is witty, well thought out and filled with interesting facts and sensible arguments. Echols’ writing talent is evident and hopefully he will employ this skill in future books.

Write your review

recommended

Arts & Culture

Arts & Culture

The Coptic Museum: The History of Egypt to the Tunes of Psalms of David

arts & culture cairo museums +4 Health & Fitness

Health & Fitness

Egyptians in the 2024 Summer Olympics

Egyptians in the Olympics Olympics +1 City Life

City Life

Weekend Guide: Bazar by Sasson, Memo, The Cadillacs, Heya Bazaar, Dou, Nesma Herky & More

Concerts The Weekend Guide +2 Arts & Culture

Arts & Culture